Welcome to the blog for The Mess We’re In – Managing the Refugee Crisis which each week provides a section from the book. One Chapter a week. This week is from Chapter 6 which details the permanent solutions for refugees and discusses the costs and benefits of migration in general.

Migration Issues

Migration Amounts

United Nations data shows that migrants made up over 28% of Australia’s population in 2015. This is quite high in the developed world. Migrant percentages in 2015 for other OECD countries include: 22% in Canada, 15% in the USA and Germany, 13% in the UK and 12% in France. In general, the developing world has much less immigrant populations: less than 1% in Mexico, Nigeria and 0.1% in Indonesia. Other relatively low migrant populations exist in Russia (8%), Iran (3%) and Japan (2%). Many of the rich oil states including the United Arab Emirates (88%), Kuwait (74%) and Saudi Arabia (32%) have large migrant worker populations.

Demographic Ignorance

As is the case in many countries, the size of Australia’s migration program is not widely known by the general public. This has been supported by a number of studies over the past fifty years1. One cause of the ignorance may be that demography is not widely taught in Australia, another is that the figures are not easily accessible, or understood once accessed. Gary Freeman, an American scholar, suggests this is because most liberal democracies run immigration rates higher than the electorate prefers2.

The argument continues that immigration produces concentrated benefits and diffused costs, resulting in vested interest groups lobbying for higher immigration rates. The concentrated benefits are in the forms of new customers for housing developers, more customers for retailers, and cheaper labour for employers. The diffused costs include increased housing costs, increased congestion, lower wages and less environmental amenity.

Life Boat Ethics

Life boat ethics is a metaphor for resource distribution proposed by Garrett Hardin in 1974. Hardin was the American ecologist who had famously brought William Forster Lloyd’s ‘Tragedy of the Commons’ metaphor into popular consciousness in 1968. Life boat ethics was the next generation of Hardin’s exploration into population and immigration. It can be used to provide a perspective on the case for limiting migration amounts (including asylum seekers).

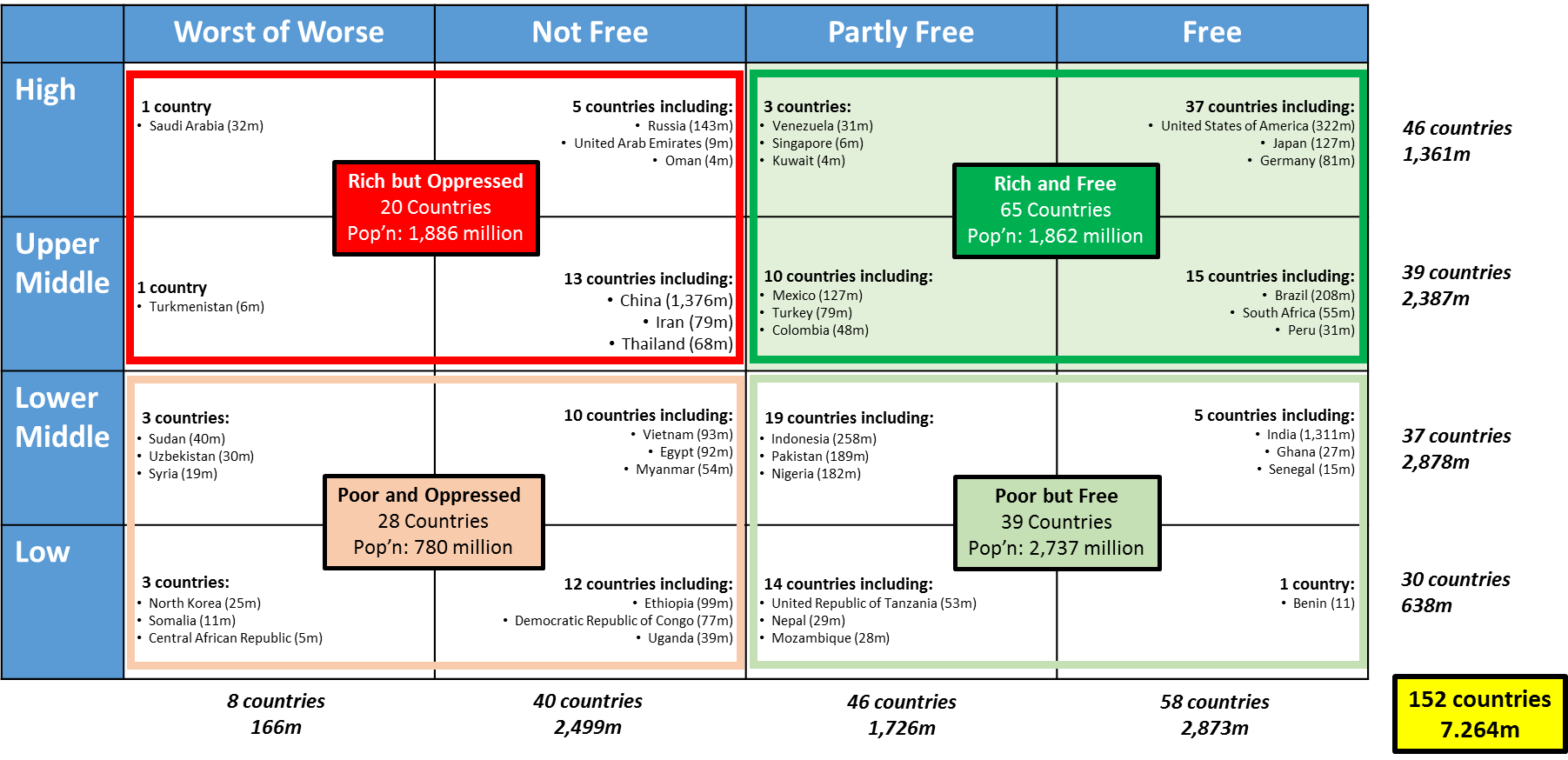

If the world is roughly divided into rich and poor nations, about 80% of the population would be poor and only 20% would be rich. Metaphorically, each rich nation can be seen as a lifeboat full of comparatively rich people. In the ocean outside each lifeboat swim the poor of the world. The metaphor then asks who should get in, or at least have a share of some of the wealth. What should the lifeboat passengers do?

- Firstly, the limited capacity of the lifeboat must be recognised. For example the land, water and other resources of a nation have a theoretical carrying capacity. Hardin asked the reader to assume a life boat representing the USA with 50 people in it, and a carrying capacity of 60. The example then poses the question of what to do with 100 people of the poor nations swimming in the water outside.

- Option 1. Take on everyone. Helping all in need would result in taking all 100 people onto the boat. The result would be having the life boat designed for 60 carrying 150, swamping the boat and drowning everyone.

- Option 2. Take on ten people to fill up capacity. In this case, Hardin asks which ten would come on board? Are the ‘best’ ten chosen or are the first come taken? What is said to the other 90? Hardin then points out that if all ten spots are taken, putting the life boat at its theoretical maximum carrying capacity, the safety factor of a buffer amount under the carrying capacity is lost. Thus, mishaps affecting crops such as a drought or a new plant disease could have disastrous consequences.

- Option 3. Take on less than ten. If a small buffer is preserved to provide a carrying capacity safety factor, then survival of the life boat is possible but only when constantly guarding against boarding parties.

- Hardin argued that Option 3 was clearly the only means for survival. He also recognised that it is morally abhorrent to many people. His response was to tell them to, ‘get out and yield your place to others’.

The much higher fertility rates of the poorer nations also impact the life boat model. The richest 20% of nations are doubling every 80-odd years, whereas the poorest 80% are doubling every 30-40 years, twice as fast. The growth rates imply that the difference in average wealth between the rich and the poor nations will most likely increase. In ‘sharing with all according to their needs’, ‘their needs’ are determined by population size, which in turn is determined by the fertility rate. This is a sovereign right of every nation, poor or not. The burden of sharing (be it foreign aid or immigration into rich countries) on rich nations will continue to increase until the population growth of the poorest nations is stabilised as they go through the demographic transition.

Mutual Regard

Collier posits that mutual regard is reduced when immigrants remain outside the mainstream society. Although a diversity of migrants creates a greater diversity, a loss of mutual regard will have detrimental impacts on public institutions that require cooperation to best operate3.

The Liberal Paradox

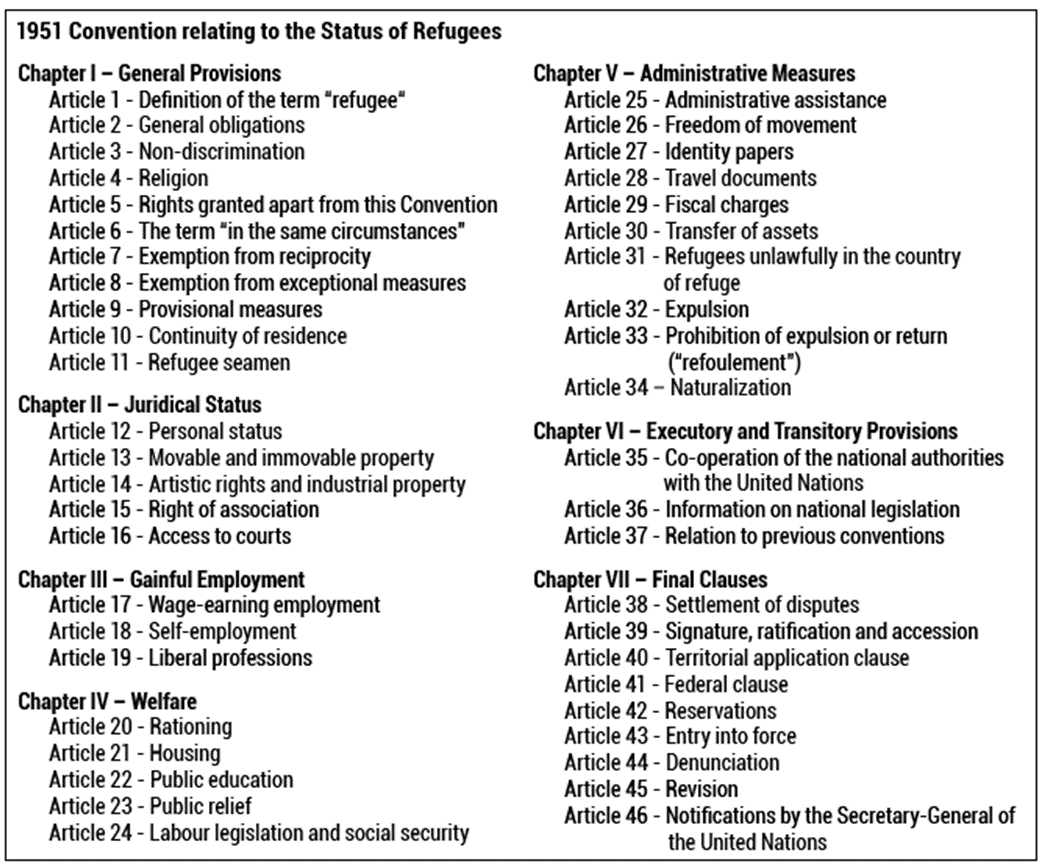

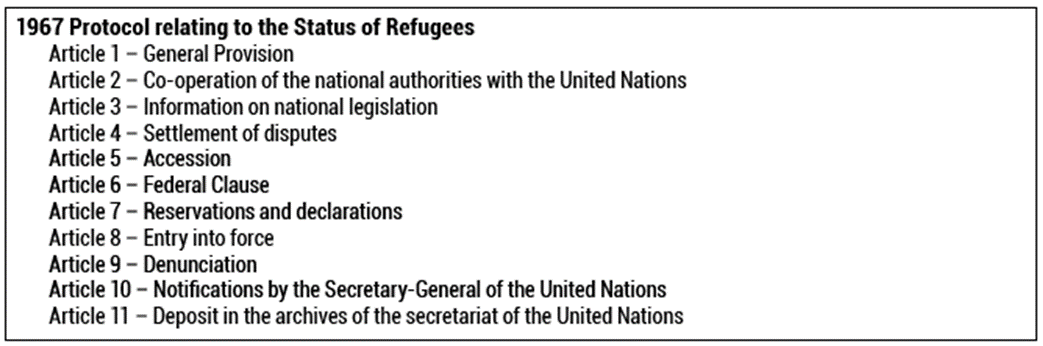

Along with an increase in immigration, since World War II liberal democracies have expanded the rights for marginal and ethnic groups, including foreigners4. As we have seen, this originated with the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948. These expanded rights have constrained governments in their attempts to control borders and exclude specific individuals or groups from membership in society.

The continued immigration drive by the Push and Pull Factors combined with the expanded rights since World War II have highlighted some difficulties liberal democracies are having with controlling immigration. In 1992, academic James Hollifield raised the ‘liberal paradox’: How can a society be open for economic reasons and at the same time maintain a degree of political and legal closure to protect the social contract?5 Initiatives made by many states to regain control of their borders have included the rollback of some civil and human rights. Examples of such rollbacks include the United States’ 1996 Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act which increased restrictions on immigrants; Germany’s amendment to Article 16 of the Basic Law which restricted the blanket right of asylum; and the Pasqua and Debre laws in France of the 1990s6. Since World War II there has also been a rise in nationalist, anti-immigration movements. A prime example is the French Front National Party, but similar parties exist in many countries with high immigration.

Scholars have suggested there is a trade-off between immigrant numbers and rights. States may have more foreign workers with fewer rights; alternatively they may have fewer foreign workers with more rights. However they cannot have both. That is, more foreign workers through open labour markets, and high rights for all7. However, if not all members of a society are citizens with the same rights, many argue the society is not a truly liberal society.

End Notes:

- Katharine Betts,”Attitudes to Immigration and population growth in Australia 1954 to 2010: An Overview,” People and Place, vol. 18, no. 3, 2010: 34.

- ibid

- Paul Collier, Exodus (London: Oxford University Press, 2013), 35 of 159. IBook edition.

- James F. Hollifield, Philip L. Martin and Pia M. Orrenius, Controlling Immigration: A Global Perspective, Third Edition (United States, Standford Univerity Press, 2014), 8-9.

- ibid

- ibid

- ibid

This was taken from the 2017 book, The Mess We’re In – Managing the Refugee Crisis. It can be purchased at any book store in Australia and online, including via this link.