Welcome to the blog for The Mess We’re In – Managing the Refugee Crisis which each week provides a section from the book. One Chapter a week. This week is from Chapter 3 which outlines the options for people who have been forcibly displaced, provides an overview of mass movements since World War II, and summarises the history of asylum seeker arrivals to Australia.

Asylum seekers and refugee arrivals to Australia can be summarised in three types:

- Offshore Program, Resettled Refugees: Already under temporary protection and are being resettled in Australia from a UNHCR camp or another signatory nation.

- Onshore Program, Irregular Maritime Arrivals (IMAs): Not currently protected and arrive in Australia by boat without the necessary documents that would allow them into Australia should they not be requesting asylum. Note. The Refugee Convention specifies that travel documents are not required by those requesting asylum.

- Onshore Program, Non-IMAs. Not currently protected and arrive in Australia (usually by plane or by boat) with documents that allow them into Australia on a visa such as a tourist visa, and who then request asylum.

Arrivals to Australia via the Offshore program were already protected by their Country of First Asylum. Arrivals to Australia by the methods covered by the Onshore program are not. At the time of their arrival, people covered by the Onshore program are displaced and vulnerable.

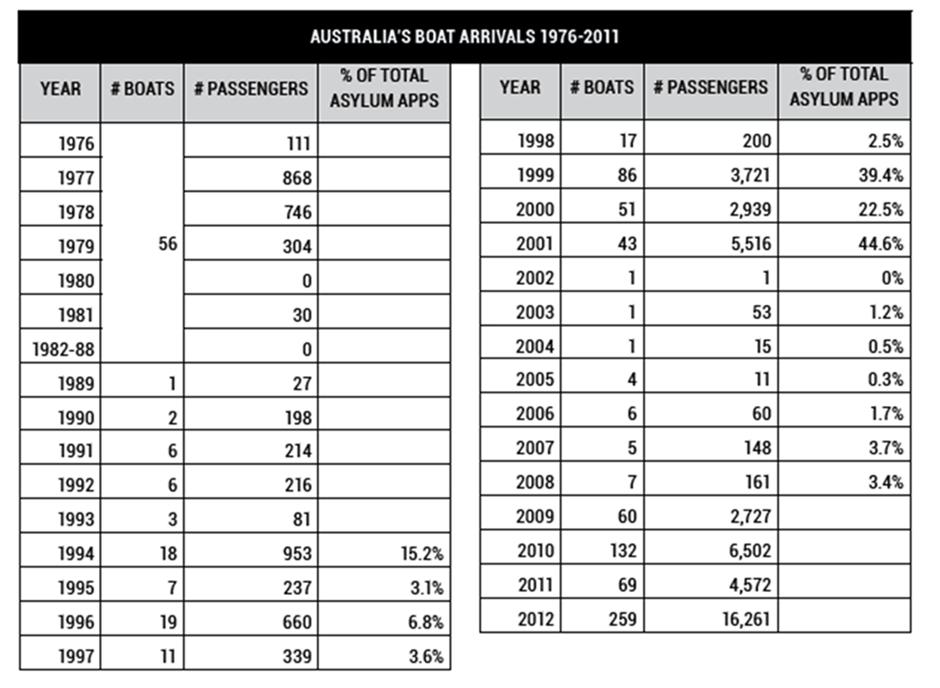

There has been much debate in Australia regarding the treatment of IMAs since the infamous MV Tampa incident of August 2001. At that time, the Howard Government of Australia refused entry to 438 would-be IMAs who were picked up by the Norwegian freighter MV Tampa. Over the preceding three years, the number of people arriving as IMAs had risen sharply from 200 in 1998 to 5,516 in 2001.

The incident proved to be a line-in-the-sand moment for the Australian Prime Minister John Howard and his government;

“Although the circumstances of the Tampa had not been foreseen it became, almost immediately, a powerful symbol of our determination to regain control over the flow of people into Australia”1.

The asylum seekers on board the Tampa were ultimately processed in New Zealand and Nauru and the incident also prompted the creation of the Pacific Solution.

Source. Project SafeCom, <www.safecom.org.au/pdfs/boat-arrivals-stats.pdf> accessed July 30, 2016

The Pacific Solution was an initiative to process and determine all IMA refugee claims in regions outside Australia. From 2001 these claims were processed on Nauru and Manus Island. In addition to this, a policy of turning back boats attempting to arrive in Australia was also adopted. The explicit purpose was to deter people from setting out for Australia at all by clearly showing that not even the processing of refugee claims would be done in Australia.

The number of IMAs following the 2001 introduction of the Pacific Solution suggests it worked in deterring people from attempting to come to Australia by boat. The number of arrivals dropped dramatically in 2002 and stayed low until 2008. In 2008 the Australian Government, under Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, ended the Pacific Solution and the numbers once again began to rise. This rise continued until the re-introduction of similar deterrence initiatives from 2012. These initiatives being a reintroduction of the Pacific Solution in 2012 and Operation Sovereign Borders, the process of turning back boats carrying asylum seekers to the country from which the boat departed, in 2013.

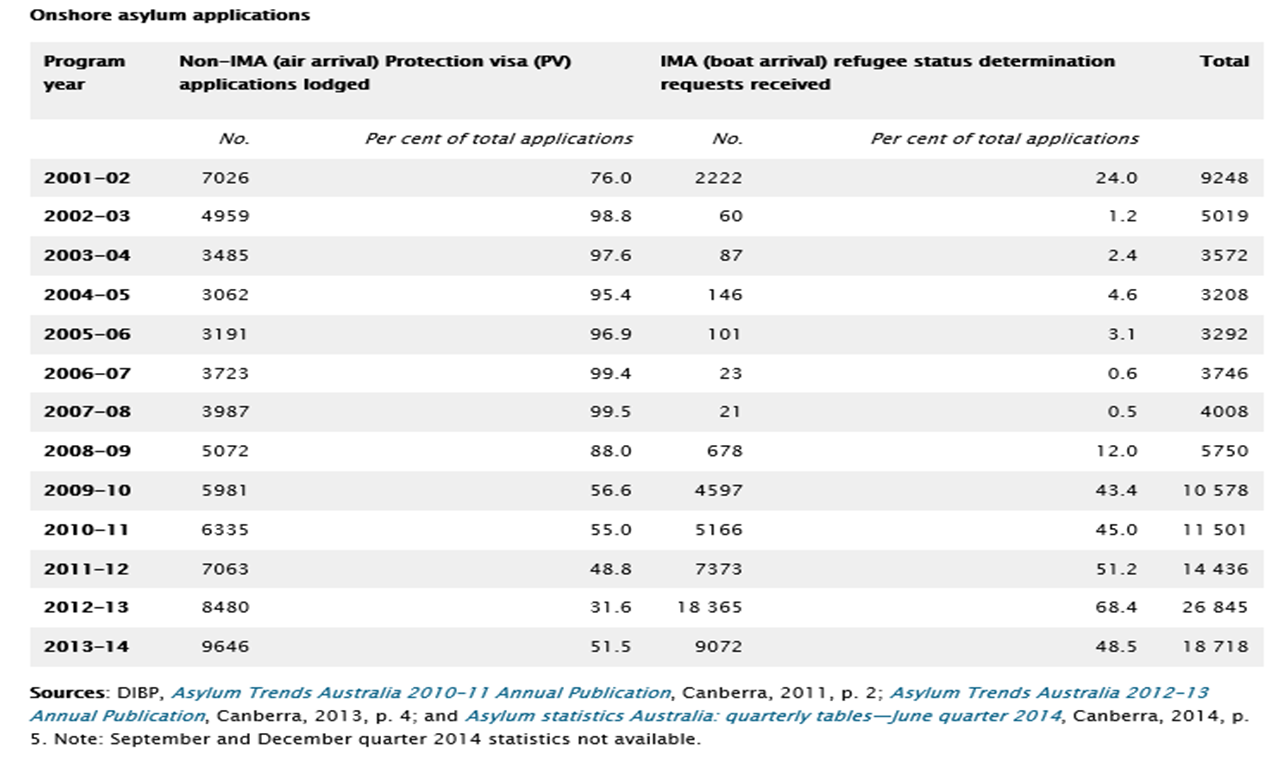

Over the past 15 years, 72,000 (or 60%) of the Onshore arrivals have been through the Non-IMA channel, with 48,000 (or 40%) arriving as IMAs. However, the year-on-year experience has fluctuated significantly. Using financial year data provided by the Parliament of Australia2 between 2002-03 and 2007-08 the average annual number of IMAs was 73, about two per cent of Australia’s total asylum seekers for that time. In 2012-13 it peaked at over 18,000 with the average across the three year period 2011-12 to 2013-14 being over 11,000, about 58 per cent of all asylum seeker requests. The variation in the number of IMA arrivals has a direct link to Australia’s policies regarding the protection provided to IMA asylum seekers. This is a contentious policy area explored further in Chapters 9 and 10.

Source: Asylum Seekers and refugees: what are the facts? Parliamentary Library Research Paper (2 March 2015). DIBP, Asylum Trends Australia 2010-11 Annual Publication, Canberra, 2011, p 2; Asylum Trends Australia 2012-13 Annual Publication, Canerra, 2013, p 4; and Asylum statistics Australia: quarterly tables – June quarter 2014, Canberra, 2014, p 5. Note: September and December quarter 2014 statistics not available.

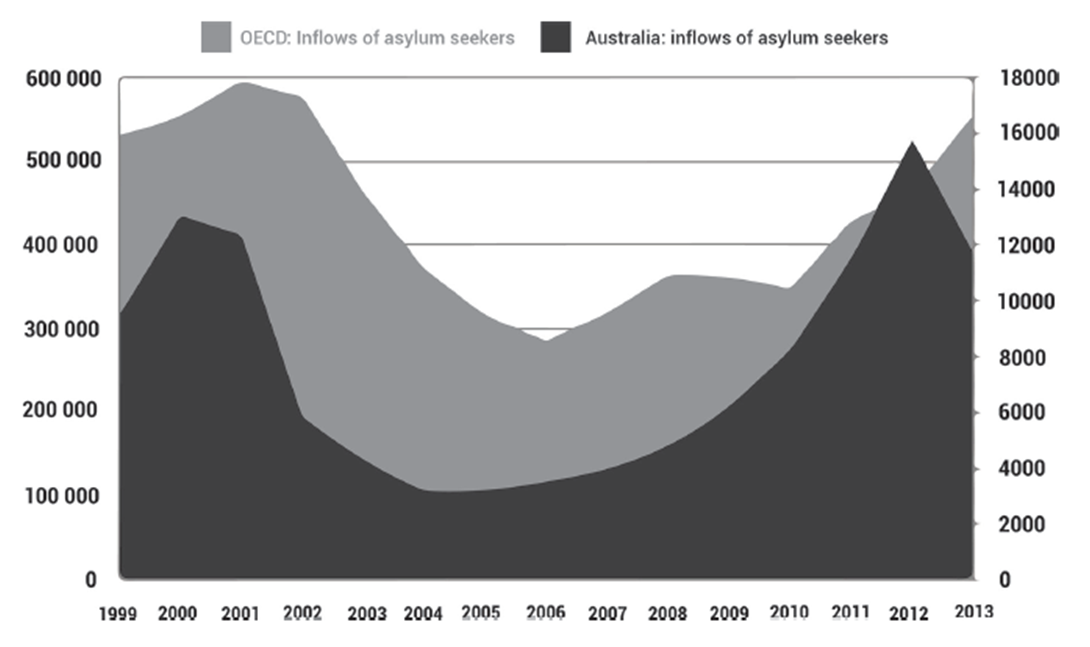

Over the same time period, the number of asylum seekers arriving in Australia has been a very small fraction (between 0.5-2.3%) of the total worldwide number of asylum seekers (700,000 to 1.8 million). The fluctuation in application volume follows a similar pattern, although Australia’s range varies more than the global variation. In the years since 1999, Australia’s range varied 800% (between 2,000 and 16,000) whereas the OECD has varied about 200% (between 600,000 and 300,000).

Data Source: Australian Parliament, Parliamentary Library.

The fact the worldwide volume of asylum seekers is much larger has been used by both sides of the debate. Opponents to the current policies (those tough on IMAs in order to deter their arrival to Australia) point to Australia’s small percentage share of the worldwide asylum seeker numbers as evidence of the country not doing its part to adequately share the burden. Supporters of the current policies use those same figures as evidence of the potentially overwhelming numbers that are in desperate need and could arrive on Australia’s shores if Australia was perceived as a soft target.

Given Australia’s island geography and remote location it is able to control its borders like few other countries. This leads to debate as to what its obligations are in relation to acceptance of asylum seekers. The debate centres around whether Australia should be obligated to accept people who could more easily have sought sanctuary elsewhere. On one hand, there is the obvious reluctance to turn people in need away, and the desire to help all those who need it.

On the other hand, accepting people who could have more easily sought asylum elsewhere creates an incentive for others to try the same approach. This promotes dangerous travel, often through people smugglers. The relative attractiveness of requesting asylum in one country, such as Australia, over another indicates a difference in protection standards and potential outcomes based on the location of application for asylum. The differences in the quality of life a refugee experiences based on where they request asylum is considered by many as a limitation of the current system (explored further in Chapter 5).

End Notes:

- John Howard, Lazarus Rising (Revised Edition), (Australia: HarperCollins, 2013), 325 of 765, iBooks edition.

- Janet Phillips, “Asylum seekers and refugees: what are the facts?,” Australian Policy Online 2 March, 2015).

This was taken from the 2017 book, The Mess We’re In – Managing the Refugee Crisis. It can be purchased at any book store in Australia and online, including via this link.