Welcome to the blog for The Mess We’re In – Managing the Refugee Crisis which each week provides a section from the book. One Chapter a week. This week is from Chapter 5 which details the countries of asylum, outlines the process or Refugee Status Determination as well as the problems with the Refugee Convention.

Nations that can help

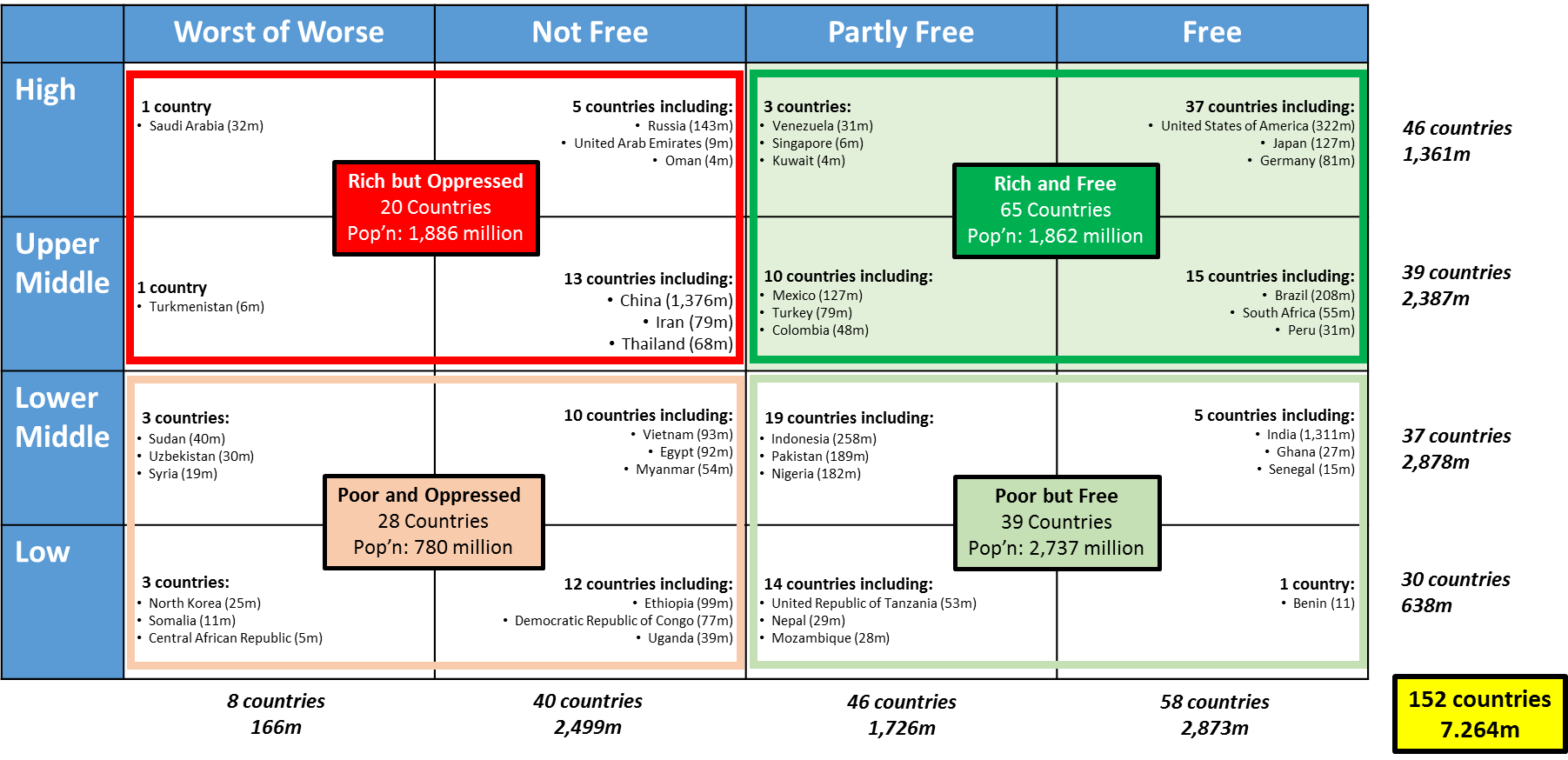

There are 65 countries of over one million in population that have both a high or upper-middle income and are categorised as Free or Partially Free by Freedom House’s Freedoms of the World Index. They have a combined population of almost 1.9 billion roughly 25% of the global population. Three of these – Lebanon, South Africa and Turkey – are Countries of First Asylum and already overwhelmed with an influx of refugees.

The other 62 are countries that possible approach options are intended to be adopted by. For brevity they will be referred to as the 62 Countries of Second Asylum. Many of these countries already receive a large amount of refugees but others do not. These countries arguably have the resources and societies to positively impact the plight of the world’s Forcibly Displaced People.

* Note: Excludes Côte d’Ivoire, Kyrgyzstan, State of Palestine, China Hong Kong SAR, Puerto Rico and 23 million living in other non-specified areas due to incomplete data.

*Note: South Africa, Lebanon and Turkey are Countries of First Asylum.

This book refers to the other 62 as Countries of Second Asylum.

Factors Driving Countries of Asylum

Four factors appear to influence the destination for refugees.

- Proximity to home. This enables an easier return home should the situation improve. It’s also likely to be more culturally similar and have a larger diaspora from the homeland.

- Ease of access, both in terms of travel and barriers to entry. Generally it is easier to arrive at a Country of First Asylum. Until 2015, the policies of the more distant Countries of Second Asylum were increasingly restrictive in accepting refugees from Countries of First Asylum. An example of this was the ‘no advantage principle’ adopted by Australia as it reintroduced the Pacific Solution following the Houston Report.

- The standard of living likely to be experienced as a refugee, an example being the ability to work.

- The probability for successful resettlement and the quality of life if accepted in the destination country, demonstrated by the mass movement to Germany when it opened its borders to Syrian refugees.

These factors generally lead to a distribution of refugees that places excessive strains on attractive nations which, at their extreme, may lead to social or economic breakdown causing further disruption and displacement. As of the end of 2015, the most obvious strain is that borne by Lebanon, a Country of First Asylum for Syrian refugees with over 23 refugees per 100 citizens. Germany incurred a high strain as a resettlement nation in late 2015. In the midst of over 1 million refugees arriving in a matter of months, it strongly urged its neighbours to share its burdens.

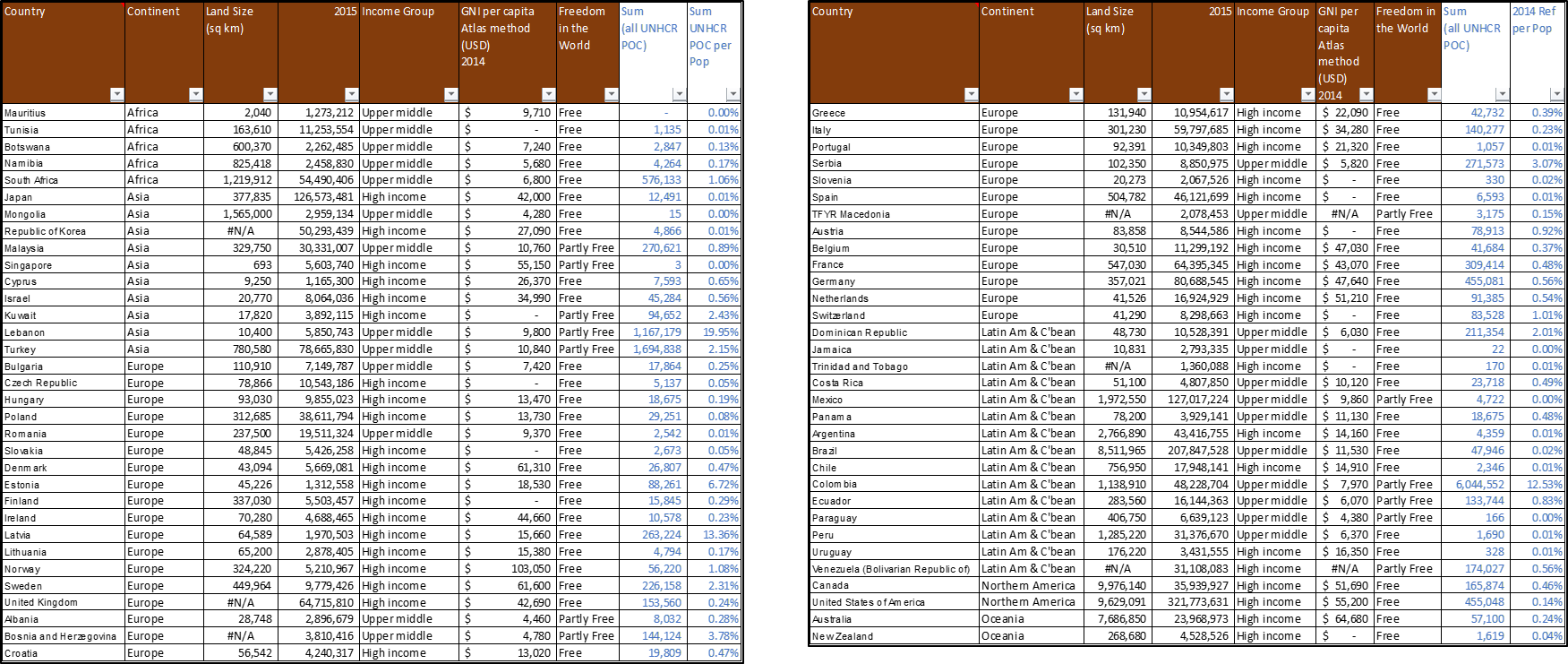

Just how many refugees a nation can successfully support is also dependent on many factors. Two critical factors are its size and wealth. Larger and wealthier countries can absorb greater numbers of people. Another factor is the level of support it provides. Poorer countries like Lebanon, Turkey, Pakistan and Kenya do not provide the same financial and material support for refugees that rich countries like Germany, Sweden, the USA and Australia (for some refugees) are able to provide. An example of this is welfare payments. Australia provides Asylum Seeker Assistance to those who are qualified to live in the community. Such payments are not provided in the Countries of First Asylum that are poorer and have many more refugees to support.

Accepting this differential of support there exist three factors that appear to influence how many refugees a willing country could absorb without undue risk to its stability.

- Host nation population: an intake proportional to the overall population appears a sensible consideration in terms of maintaining culture and being able to absorb the additional people in existing infrastructure.

- Host nation wealth: an intake proportional to a nation’s wealth. The higher the wealth of a nation (measured GNI per capita) the more resources it has to support any intake.

- Host nation land and population density: nations with smaller land size, and those already crowded, may arguably be less able to absorb an intake.

Standard of Protection

The experience of a refugee in a poor Country of First Asylum such as Lebanon or Turkey in comparison to wealthy Country of Second Asylum such as Germany, Australia or the US is vastly different. This difference in experience is based on two key factors: the quality of life as a refugee; and the probability of resettlement into a Country of Second Asylum. It is arguably this difference that provides the motivation for some people to undertake secondary movement from a Country of First Asylum to a Country of Second Asylum.

- Quality of Life as a Refugee

The majority of refugee-producing countries are poor or are in the midst of conflict. These include countries such as the Central African Republic in Africa or Syria in the Middle East. As a general rule the neighbouring countries – at least those willing to accept refugees – are also relatively poor. The Central African Republic’s neighbours including South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo have a very low per capita GNI as do the main destinations for Syrian refugees in Turkey, Jordan and Lebanon. Given the large number of refugees and the limited infrastructure and financial resources, these countries are not well placed to sufficiently provide for the influx of refugees. Often the UNHCR and other voluntary organisations are called in to provide support and protection. Such support is essentially basic shelter and food with limited work opportunities for adults and educational opportunities for children. Refugees in these countries have the choice between remaining in a UNHCR camp with limited opportunities for education or work, or trying their chances in the main cities without any formal support.

Many refugees prefer to remain in the Countries of First Asylum for reasons including cultural similarity, increased diaspora and proximity to their home to ease the return process. However, some refugees prefer to head toward a more developed country such as Germany, Australia or the United States. For those who are able to make the journey, the Refugee Convention dictates that as refugees they must be supported to a level similar to citizens of the host nation. Countries of Second Asylum with a comparatively high social net like Australia and Germany thus become much more attractive than less wealthy Countries of First Asylum.

An example is an asylum seeker to Australia who arrives with a visa authorising their entry. A refugee in Australia on a permanent protection visa is provided unemployment benefits (if not working) and rental assistance. Although modest (approximately A$570 per fortnight in 2012) these benefits offer much more autonomy compared to what is provided to refugees in Lebanon. Additional, non-financial support is also provided in the form of orientation, assistance with sourcing accommodation and introduction to community and settlement groups and services. The full level of services is detailed in Chapter 9. Of course, this assistance is only provided to a very small subset of refugees. With the re-introduction of the Pacific Solution in 2013, asylum seekers arriving without a visa to Australia are now placed into Offshore detention with little likelihood of ever settling in Australia.

- Probability of Resettlement into the Country of Second Asylum

The number of refugees who are resettled to a Country of Second Asylum is very low in comparison to the total number of refugees. In 2014, less than 1% (103,390) of the total number of refugees were resettled. For asylum seekers hoping for resettlement into a Country of Second Asylum, the odds are very slim for those who remain in a Country of First Asylum. Relatively few refugees are submitted for resettlement on the back of UNHCR processing. Of these, less than 10% are taken each year.

In contrast, arriving at the desired Country of Second Asylum often means the asylum seeker will be processed by that country. If their refugee status is confirmed during the RSD then the individual can expect eventual permanent residency. Although Australia has removed this outcome for unauthorised arrivals, it is still an avenue in many countries – most notably Germany and Sweden during 2015. As failing the RSD does not necessarily result in compulsory expulsion, there are still advantages to arriving at resettlement countries without strict border control policies.

This was taken from the 2017 book, The Mess We’re In – Managing the Refugee Crisis. It can be purchased at any book store in Australia and online, including via this link.